Now even rocks are racist.

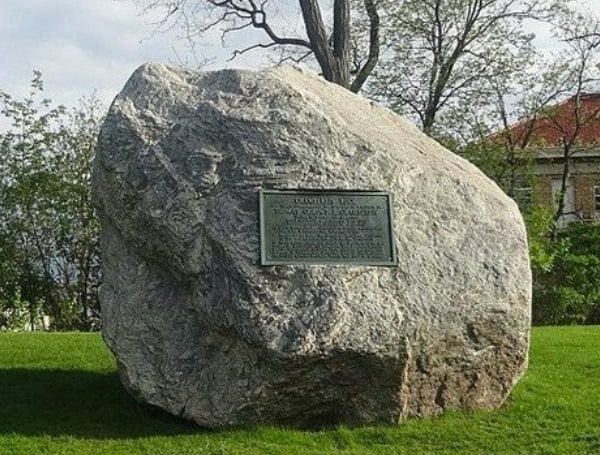

The University of Wisconsin last week moved a 42-ton, 2-billion-year-old boulder that had sat in the same spot for 96 years because some viewed it as a symbol of racism.

That was despite the fact that no one could find an example that the university had ever referenced the rock in an allegedly racist context in nearly a century.

An article put out by the campus communications office noted the rock was a “glacial erratic.” The National Snow and Ice Data Center in Colorado states that such rocks were hauled over the earth by glaciers as the ice formations shifted, and then settled as the glaciers melted.

Accordingly, “the rock has immense teaching and educational value in addition to its scientific importance,” the campus news service noted.

This particular boulder was dubbed Chamberlin Rock, named for Thomas Chamberlin, a prominent geologist in his time who also had served as UW president from 1887 to 1892.

The boulder was moved to its previous location, near the crest of a hill, in 1925.

Yet last year, amid all the racial unrest, it became, as the race-baiters say, problematic.

The campus news service reported that the rock was “a painful symbol of racism to generations of students,” particularly black and indigenous students. The Black Student Union called for its removal last year because it was a symbol of “anti-blackness.”

The group, in an Instagram post last year, uncovered a 1925 Wisconsin State Journal article that referred to the boulder as a “(N-word)head,” which reportedly was a reference to its shape and color at the time.

Interestingly, in that post, the Black Student Union not only called for relocating the rock, but also a statue of Abraham Lincoln because he, too, was not “pro-black.”

There is no evidence, however, based on the campus article, that Chamberlin himself was “anti-black.”

University administrators gushed over the black and indigenous students who demanded the rock be removed.

“It took courage and commitment for the Wisconsin Black Student Union to bring this issue forward and to influence change alongside UW’s Wunk Sheek student leaders,” Vice Chancellor for Student Affairs Lori Reesor said.

“In the midst of demands for justice following George Floyd’s murder last summer, the students wanted change on campus and they worked hard to see this through. While the decision required compromise, I’m proud of the student leaders and the collaboration it took to get here.”

Yet, the campus news service pointed out, “UW–Madison historians have not found evidence that the racist term attached to the rock in the 1925 newspaper article was used in any capacity by the university.”

Last September, the campus student newspaper reported, “UW Tribal Relations Office Director Aaron Bird Bear, who discusses the rock’s offensive nickname during his regular cultural landscape walking tours of campus, wrote in an email that UW’s staff found one instance of the offensive term in a 1925 Wisconsin State Journal article about the unearthing and subsequent relocation of the boulder.”

“The reporter used the offensive term as a generic reference to the geological feature. A year after the newspaper article was published, the rock was named after Chamberlin,” the article noted.

Moreover, the State Journal reported in November that the rock’s offensive nickname “appears to have fallen out of common usage by the 1950s.”

So, in other words, the nickname was never used by the university, was used only one time in 1925 in reference to the rock as far as anyone can tell, was a phrase that no one in that area has regularly uttered in more than 60 years but yet was kept alive only by people who felt offended.

Still, it had to go – at a cost of $50,000.

And despite this history, the university offered comments such as those by Gary Brown, the director of campus planning and landscape architecture, who said the removal “prevents further harm to our community.”

Juliana Bennett, a senior and a campus representative on the Madison City Council said getting rid of the boulder allows BIPOC students to “begin healing.”

She told the Associated Press, “Now is a moment for all of us BIPOC students to breathe a sigh of relief, to be proud of our endurance, and to begin healing.”

Yes, the rock is gone. UW can now breathe and heal.

Support journalism by clicking here to our gofundme or sign up for our free newsletter by clicking here

Android Users, Click Here To Download The Free Press App And Never Miss A Story. It’s Free And Coming To Apple Users Soon.

You have to be injured first in order to let the healing begin. The rock didn’t hurt anyone, as it has been stationary for most of its 2 billion years and can account for its whereabouts during the time any of the false claims of injury were made. Stop trying to placate the multitude of whiners. They are never satisfied with any gestures and are already looking for more things to get rid of in order so that they can “heal”.

This is so ridiculous- if you were/are a student at this University, time to leave, quickly.