August 22, 2020 By: Martin Fennelly TAMPA, Fla. - How hard up are we for sports when a 10-part documentary on someone whose greatness came a qu

August 22, 2020

By: Martin Fennelly

TAMPA, Fla. – How hard up are we for sports when a 10-part documentary on someone whose greatness came a quarter-century ago holds us in suspense?

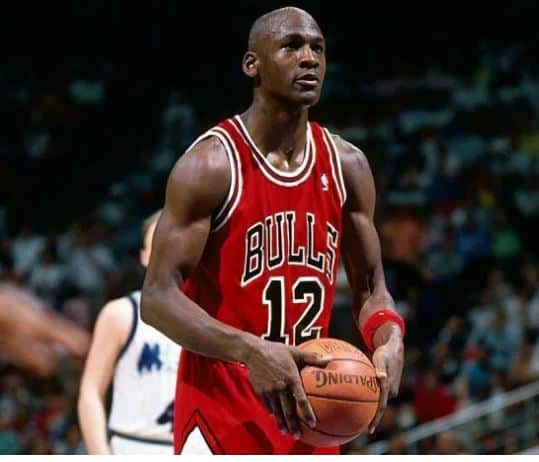

I don’t know about you, but it happened to me. I sat there with my mouth open – for five Sundays across five weeks, I tuned in to ESPN to watch The Last Dance, all about Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls pursuit of a sixth NBA title in eight seasons, and Jordan’s pursuit of greatness, day in and day out. I knew how it would turn it, all of it, but I couldn’t take my eyes off it.

I can’t explain why this film transfixed me. And I have not been sitting around arguing with myself or anyone else about who was greater, Jordan or Kobe, or Jordan and LeBron, or Jordan or Babe Ruth, or Jordan or Muhammad Ali. That is for someone else.

But I was reminded that I lived in the Jordan years, and damn, they were fun.

The documentary isn’t definitive, a portrait of the man in full. Jordan clearly had too much control in this project. You don’t really learn that much about his life outside of basketball, maybe because he didn’t have one. You never see his wife in the film (or wives). You don’t see any of his children until the final episode. I don’t really know any more about Jordan than I did going in, except maybe that he could

Drop the F-bombs. But I suspected as much.

This was not a perfect man. Not even close. But in a time when there are no live sports, save for a NASCAR race run at an empty track or charity golf matches on desolate tracks of green grass, watching Michael Jordan, again and again, soaring over all of us, was a grabber. I could watch Jordan highlights, the dunks, the buzzer-beaters, the inside moves, the trash talk, on a continuous loop for the rest of my life.

Could he have been a better man? Yes. Was he cruel to opponents? Yes. Did he pull the wings of off teammates? Absolutely. Was he consumed by winning and so driven he fed off slights, real and imagined? You know the answer.

He wasn’t Ali. The documentary details the time Jordan refused to dip a toe in a U.S. Senate North Carolina which pitted an African American against the cracker Jesse Helms, with Jordan noting “Republicans buy sneakers too.” It’s hard sometimes to think about how little Jordan used his huge platform, how much more he could have done.

But he was not that kind of man. He was an athlete, nothing more, and must be taken and admitted as such.

On the other hand, he was so much fun to watch, So much damn fun.

My Jordan stories are all on the periphery, which is how much of us live anyway. But I think they’re instructive. They speak to the sweep and swirl of Jordan. They are tiny stories, but they add up to how I think of him, what I think of him, why I think of him.

I remember January 1988. I was in Chicago to cover the NFC Championship game between the Chicago Bears and the San Francisco 49ers. But Jordan and the Bulls are playing at Chicago Stadium on a Friday night. So, I took a cab to the decrepit old barn, nestled in one of Chicago’s worst neighborhoods, and scalp a ticket, a good ticket, $100 worth, so I can sit right behind the Chicago bench and watch the man at work. Bucket list,

The Bulls lost to the Jazz, and Jordan, as I recall, didn’t even get 30 points, but I could hear him in the bench huddles. I could see the sweat on his forehead. Of course, I couldn’t get a cab after the game. Hadn’t thought of that. I walked back to my downtown hotel with my life passing before my eyes each step of the way. But as my head hit the pillow that night, I thought of Jordan dunking over Karl Malone, right in front of me.

Another story is from when Jordan decided to retire after three NBA titles to become … a baseball player, He was in Sarasota, taking his spring cuts with the White Sox, watched by hundreds, thousands of media. I was part of that circus. I remember being in the White Sox dugout when Jordan patted his bat with a pine tar rag. After he did, a White Sox batboy picked up the pine tar and stuffed it in his back pocket for a souvenir. That is what it was like.

After Jordan returned to basketball, I went to see him play the Magic in Orlando. I brought my wife with me. She didn’t know much about Jordan or even sports, but I decided she should see the man up close. So, against all ethics, I snuck her into a courtside press-row seat for part of the game to watch Jordan. After the game, my friend and co-worker asked her to help him with his story and get some Jordan quotes for his story from the Bulls locker room. She was a journalist, after all, albeit it a copy editor. She said sure. I gave her my notebook.

She was gone a half hour. We kept wondering where she was as his deadline ticked down. Finally, she showed. “Oh, Michael looked so good” We smiled. “He was wearing this burgundy suit with a paisley tie.” We asked him about the quotes, “He was so nice and well-spoken.” Our smiles began to fade. “I mean, that suit.” Finally, we had to ask, loudly: “We’re on deadline. DID HE SAY ANYTHING?” She looked down at her notebook and said Jordan said it was a good game. “And?” She smiled and told us she forgot to write it down.

That was Jordan. We all forgot to write it down. We were too close to the sun. Cynicism faded. We had his game, a game that will never be seen again, and we were lucky to be around it. He wasn’t the perfect man, but he was as good as he could be given the circumstances of being, well, him.

My one last Jordan story is from 1998, late in his second run of three consecutive NBA titles. I was in Atlanta to watch the Bucs play the Falcons, but on a Saturday night, Jordan, with retirement looming, again, was with the Bulls to play the Hawks, at the monstrous Georgia Dome, before 62,000 people, the largest crowd to ever see an NBA game. I wangled a press pass. It was Jordan. I and to see him one last time. They could have sold 20,000 more tickets that night. Jordan dropped 34 points on the Hawks, I think. Ticket sales helped raise money for tornado-victims relief.

Anyway, after the game, I stood in a mob or reporters in a hall. Jordan popped out, surrounded by yellow-shirt security, to talk about the game. But he seemed distracted. He kept looking down the hall. Something had caught his eye. He answered our questions, then was whisked back inside. I lingered. A few minutes later, Jordan came out a door down the hall. He bent down and shook hands with what had been distracting him as he did his interview: a young boy in a wheelchair. Jordan whispered to an underling, who ducked back into the Bulls locker room and emerged with Jordan’s No. 23 jersey. Jordan signed it and handed it to the boy, whose father fought off tears.

Then Jordan was whisked down the hall by the yellow shirts, disappearing into the night.

Maybe we don’t know him. Maybe we never knew him. He was the greatest basketball player I ever saw. He burned as bright as the sun. Maybe he wasn’t the man he should have been. But he didn’t do badly considering. I’d watch another 10-part documentary on him tomorrow. Just to see him dance one more time.