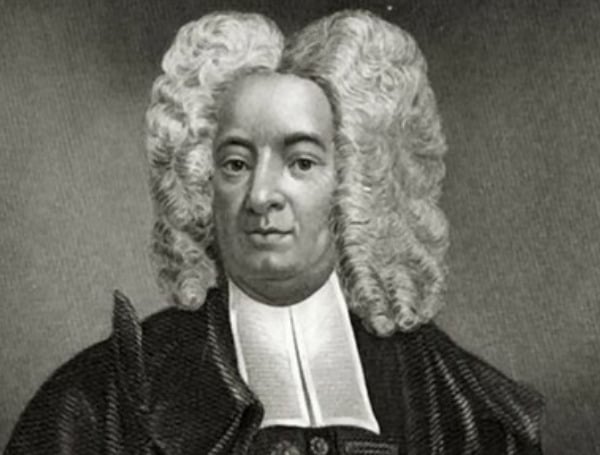

By Edward Cifelli Cotton Mather, the cantankerous Boston minister who has been saddled with a big portion of the blame for the deadly Salem Witch

Cotton Mather, the cantankerous Boston minister who has been saddled with a big portion of the blame for the deadly Salem Witch Trials in 1692, was a hero in 1721 when he espoused inoculations to fight off the deadly smallpox epidemic that had reappeared in Boston that year.

The anti-inoculators were so fierce and ferocious in their opposition, however, that one of them hurled a homemade bomb through Mather’s bedroom window one November night.

It came with a message: “COTTON MATHER, You dog! I’ll inoculate you with this!”

What exactly had Mather done to deserve such treatment?

For starters, he was smart enough to recognize the recurring pattern of smallpox epidemics in Boston. He had calculated that from 1630 the disease came back every twelve years.

He was expecting the next attack to begin in 1714, but it didn’t come that year, which drove Mather to speculate that the 1713 measles epidemic that had claimed his wife and three of his children had somehow altered the smallpox pattern.

Everyone in Boston, however, feared its deadly return from one year to the next that decade, and then in 1721, it hit again with a vengeance. In all nearly 6,000 people were infected that year, about half the city, 844 of whom died, according to Kenneth Silverman’s Pulitzer prize-winning biography, The Life and Times of Cotton Mather (1984).

But Mather did more than simply detect a pattern. Drawing from successful inoculation accounts published by the British Royal Society and adding word-of-mouth testimonies provided by his African servant, Onesimus, he published his theory of inoculations.

The evidence was sufficient, Mather argued, to begin a wide program of life-saving procedures—but his arguments fell largely on deaf ears.

However, through the work of a respected Boston physician, Dr. Zabdiel Boylston, an unknown number of what may be called “Mather’s inoculations” were administered during the summer of 1721 throughout the city and surrounding areas.

There was hot disagreement, but the general public had begun to be educated to the theory and implementation of protection through inoculation, the very same principles that would become widely accepted over the next three centuries.

Mather’s critics were loud, violent, and persistent, however, very slow to accept the controversial theory. And many never did. They worried that inoculation wouldn’t stop the disease but would instead worsen it. They called Mather and the other inoculators hypocritical and authoritarian.

And they dragged out their most reliable all-purpose argument: smallpox was a divine judgment against a sinful people. And sinners always got what they deserved.

History has corrected the judgment against Cotton Mather in this 1721 political-scientific battle over infectious disease. It has recognized the rightness of his crusade for inoculation against smallpox—and by extension against countless other deadly diseases from measles to polio to Covid-19.

There is no longer any scientific dispute about inoculations or immunizations, what we call vaccinations today: they have saved millions of lives and will save millions more as people line up one by one, roll up their sleeves, and get their shots.

All of this due to the tireless work of an unlikely spokesman for science, the Rev. Cotton Mather, the most puritanical of all the 17th-century New England ministers.

Support journalism by clicking here to our gofundme or sign up for our free newsletter by clicking here

Android Users, Click Here To Download The Free Press App And Never Miss A Story. It’s Free And Coming To Apple Users Soon.

COMMENTS